Full article can be viewed on the New York Real Estate Journal website.

New York, NY Denio Sturzeneker, senior supervising safety consultant for Total Safety Consulting (TSC), grew up in Belo Horizonte (Portuguese for beautiful horizon), Brazil, just steps from the bairro where the largest civil construction accident in Brazilian history occurred. The 1971 “Tragedy of Gameleira” killed 69 and injured 50 when 10,000 tons of concrete, an entire floor of a building, collapsed during construction of a new exhibition pavilion. Six years later, in 1977, Sturzeneker was born in an area still reeling from the disaster’s aftermath.

“All my life I heard the horror stories. I saw victims traumatized physically and mentally who lived just blocks from my house. Yet I knew that the accident could have been prevented. It could have been done right,” said Sturzeneker.

Though keenly aware of the dangers of construction, Sturzeneker developed a passion for the industry. At age 10, he worked for his uncle, mixing cement, cutting bricks and painting houses.

As his mother had to provide for a family of six, including three siblings and a father ill and unable to work, by the time he turned 12, Sturzeneker needed to set other interests aside to work full-time at a video store and go to school at night.

“We were a poor family, but we did what was needed to pay the bills,” he said.

After graduating high school, Sturzeneker joined his sister and her husband who had emigrated to Fort Lee, N.J. His brother-in-law soon helped him get a job with Adriatic Painting.

“A real job for $9 an hour, three times what I was making, felt like a million dollars. I believed in the American Dream,” he said.

At Adriatic he learned about concrete repairs, scaffolding, waterproofing and more. He also found time to take classes in electrical work at Hudson City School of Technology, became fluent in Spanish, and studied English as a second language.

“I had to respect the country that had given me so much,” he said.

When he was promoted to foreman at Adriatic, he decided that it was up to him to set the tone for safety on a daily basis.

“I once saw a worker drinking on a job. I saw others fall off ladders, cut themselves. I’d say, ‘We’re all adults, we’re all professionals. When you work for me, you either wear your harness or you go home,’” he said.

In 2004, Sturzeneker founded his own company, Galo Restoration, named for the Portuguese word for rooster, the mascot of his favorite soccer team. Though the firm did well for two years, with his second child on the way, the appeal of a regular salary and benefits led Sturzeneker to accept a job as foreman and safety trainer with Structural Preservation System, a building envelope company.

While there, his education continued. He studied Engineering Technology for a year at Bergen Community College. He took OSHA 500 and started to teach.

“I dove into safety,” he said, noting that exterior work presents the greatest exposure to the public.

Sturzeneker became known as the person to take on the most dangerous work.

“If a job was dangerous, they’d say ‘Let Denio do it.’ Employers loved my ‘get it done safely’ attitude,” he says. He was the foreman for the Queens Hall of Science Museum project which was rated one of the safest projects ever completed.

While at Structural, he discovered Total Safety Consulting.

“I took TSC classes. They were intense, inspirational. All the instructors were amazing,” he said, listing John Connolly who is currently his boss, the late Albert Rivera, Tom Dering and Stanley Sluska (now retired).

He also met TSC Site Safety Managers (SSMs) at jobsites and “loved the way they work.”

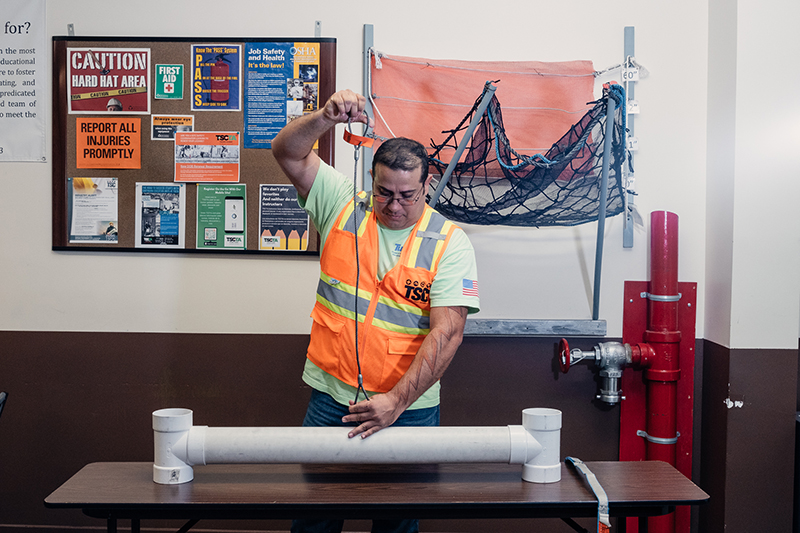

Sturzeneker applied for a job at TSC via an email to human resources, heard back within 10 minutes, and was hired a short time later as a full-time instructor at Training Academy (TSCTA) in Long Island City and now continues as a trainer in all TSCTA locations, including the Bronx and Bayonne, N.J. He reported to Tom Ferrante, and said, “Tom was like a second father to me, which meant a lot since I basically grew up without a father. I became part of the family. He said his door is always open.”

Once he joined TSC, Sturzeneker became a Certified Health and Safety Technician (CHST) following a exam requiring a year of study. He obtained over 25 licenses and certifications including: a NYS ICR 59 license to conduct safety and insurance audits; certifications as an NYC CSFSM for fire safety and another as a Health and Safety Plan (HASP) auditor; a site safety coordinator license; and many more in everything from rigging to suspended scaffolding.

Soon promoted to site safety supervisor, he still encountered resistance from workers. He said, “When you’re on a jobsite with 500 workers, you’re not there to be their friend: you’re the big brother. They have to respect you first.”

Now senior supervising safety consultant, he oversees 10 SSMs in all five boroughs. He also supervises subcontractors on jobsites installing safety equipment and has traveled to TSC’s Miami location. He interacts with all TSC divisions working “hand-in-hand” with fire safety professionals, medical technicians and Safety Supplies Unlimited (SSU), the safety equipment component.

As one of the main TSCTA instructors, he serves on a committee of curriculum developers, helping to create syllabi for classes including those related to Local Law 196.

Through TSC, Sturzeneker has worked on some of the city’s iconic projects. At Hudson Yards, a 50-story site with 300 workers, he supervised SSMs on the interior. Still ongoing is work at 1 Penn Plaza, a challenging 50-story site with 43 elevators where safety is paramount as 1,500 pedestrians pass through the area each day. Also current is LaGuardia, a five to six-year project with 1,000 workers.

Looking to the future of TSC, he calls TSC managing principals Jim and Liz Bifulco visionaries and sees TSC continuing to expand along the east coast and beyond.

“TSC has done work overseas. There are many possibilities to explore,” said Sturzeneker.

He recalls recently telling the Bifulcos (whom he says are “hands-down, the best bosses ever”) that “I don’t want to be a star, I just want to save lives indirectly.”

His love for construction and the pride of “knowing that you’re a part of a building’s history” has never dimmed. With his late mother’s advice to “Work hard. Never be late. Never give up” always in his thoughts alongside the shadow of a national tragedy, he wants most of all to “look back on the last day of a project and know that no one died, no one was seriously injured. Then you can be satisfied and know you did your job well.” You did it the right way.